A criticism of U.S. security alliances and partnerships in the Indo-Pacific had long been that these were based on bilateral relations, with little coordination among Washington’s regional allies.

But a dramatic change in the U.S.-led regional security architecture has been taking place in recent years, with the pace quickening in recent months.

New challenges affecting the region, particularly the rapid rise of China, have led to the emergence of minilateralism, or several small U.S.-led groupings of countries aiming to tackle shared security concerns.

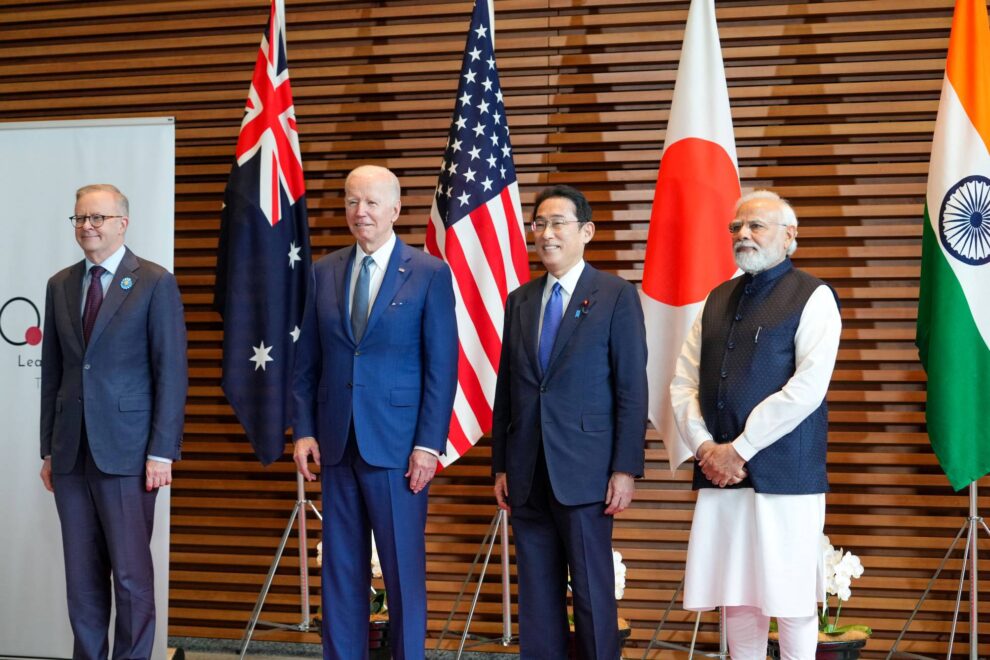

Those that are not entirely new — such as “the Quad,” which involves Japan, Australia, India and the U.S., and AUKUS, which groups Australia, the U.S. and Britain — have been solidifying their roles in recent months, while others are just taking shape such as the bolstered security cooperation between Washington, Tokyo and Seoul to counter North Korea.

All of these trilateral and quadrilateral groupings involve U.S. allies except for India, which the U.S. is working hard to draw closer, including through a recently agreed roadmap for defense-industrial cooperation.

As Washington doubles down on regional alliances and partnerships, the shift to small international groupings is “increasingly evident,” said Robert Ward, the Japan Chair at the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

“These groups often have specific strategic objectives, sometimes with overlapping defense, geoeconomic and economic security elements, and offer greater strategic agility than is often possible via larger and more formal units,” he added.

Washington’s push to bind allies and partners was on full display at the Shangri-La Dialogue Asia security conference in Singapore over the weekend.

The gathering saw U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin not only host the first four-way defense ministers’ meeting with Australia, Japan and the Philippines, it also saw the U.S. agree to set up a real-time data-sharing pact with Tokyo and Seoul on North Korean missile launches by the year-end.

Thomas Wilkins, a Japan security expert and senior fellow at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, said these moves are part of a deliberate design by the U.S. to “network” its allies, and in some cases partners, into a common front to deter challenges and realize the vision of a “free and open Indo-Pacific.”

“When Washington originally founded its ‘hub-and-spokes’ system of separate bilateral alliances in the region, it forwent the option to build an ‘Asian NATO,’” he said, indicating that the networking approach is meant to be a way to adapt to new circumstances in the region, particularly amid concerns that the regional balance of power may be tilting in China’s favor.

Although part of the Biden administration’s 2022 Indo-Pacific Strategy, U.S. efforts to build “collective capacity” in the region and reduce both redundancies and coordination challenges in its bilateral security ties can be traced back to President Barack Obama’s 2011 “Asia pivot,” which was largely triggered by the intensification of challenges posed by China.

These challenges have been most visible in Beijing’s attempt to advance its presence in the South and East China Seas, but also in promoting its own vision for a China-centered regional order, said Sebastian Maslow, a lecturer at Sendai Shirayuri Women’s College.

Speaking at the Shangri-La Dialogue meeting on Saturday, Austin highlighted two key aims of the Pentagon’s strategy to counter China.

One is the need for the U.S. to shape the strategic narrative around “a vision of a free, open and secure Indo-Pacific within a world of rules and rights,” while the other focused on boosting “integrated deterrence,” which includes the diplomatic, economic and technological “counterbalancing” of China.

“All of America’s allies and partners subscribe to these principles (with some occasional deviations), so uniting them behind this vision helps to maintain the desired order in the face of challenges posed by disruptive regional powers,” Wilkins said.

By enhancing relations with the region — be it in the form of bilateral treaty alliances, nontreaty-based strategic partnerships or small groupings of “like-minded” states such as the Quad, AUKUS and others — Washington is not only strengthening the existing security architecture but also “lending substance to its rules-based vision through tangible practical cooperation,” Wilkins added.

At the same time, analysts view Washington’s embrace of this new type of collaboration as an acknowledgment of the scale and complexity of a confluence of issues facing the region.

“Minilateralism allows Washington and its partners to operate by strategic objective, which offers flexibility and agility, allowing nations with sometimes differing geopolitical views to collaborate,” Ward said.

Another important aim of the strategy, he said, is to “build trust between these countries and so further strengthen their ability to cooperate.”

Indeed, when U.S. allies and partners are able to coordinate and work together, this reduces some of the burden on Washington to make sure they are not working at cross-purposes.

“These arrangements ensure that U.S. allies and partners can at a minimum deconflict and perhaps even offer a degree of support to each other,” said Ian Chong, a professor of political science at the National University of Singapore.

Yet there is another important reason for the ongoing shift.

Chong says some of the demands for stronger links among allies and partners may also be the result of “concerns over U.S. commitment and consistency” that arose during the administration of U.S. President Donald Trump and remain today.

Many in Washington recognize that global leadership is no longer exclusive to the U.S. and that American primacy in the Indo-Pacific cannot be sustained without greater support from its network of allies and partners.

For countries like Australia and Japan, the emerging minilateralism offers ways to not only bind the U.S. more broadly to the region but also to boost the credibility of their own deterrence capabilities in the face of China’s growing clout.

In addition, coordination among these two U.S. allies, in particular, may also be a means to provide a “stable cooperation platform” should there be lapses in U.S. commitment or engagement as a result of emergencies elsewhere in the world or a U.S. domestic political impasse, Chong noted.

Both Japan and Australia are increasingly at the center of many of the new groupings. They are also members of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), a key regional trade agreement.

And while Tokyo and Canberra reinforce their own bilateral defense ties, they also appear keen on including Manila, meaning that Japan-Australia leadership may eventually help connect many of the security frameworks in the region.

Tokyo, which has long courted the Philippines given its vital strategic location, is expected to sign a visiting forces agreement with Manila soon.

And now that the Philippines has agreed to restore and upgrade defense ties with the U.S., “a trilateral agreement with Japan would seem a logical next step, with Australia set to become a likely candidate for later inclusion,” Wilkins added.

Meanwhile, the Pentagon’s push for “collective capability” is expected to continue, with Austin announcing plans to take defense cooperation with Singapore, Indonesia and Vietnam “to the next level.”

However, whether all this qualifies as some form of a nucleus for a NATO-like security architecture in the Indo-Pacific is at this stage unlikely, Maslow said, arguing that for many countries in the region, China remains the most important trade partner.

“I doubt that we will see a consensus willing to jeopardize prospects of economic growth in exchange for closer security cooperation, at least not until U.S.-led security cooperation is matched with a credible economic and trade arrangement,” he said.

A U.S. return to the CPTPP might be a first step in this direction for regional partners to fully embrace the current momentum of counterbalancing China.

“But I see little indication that this will come any time soon,” Maslow said.

Source: The Japan Times